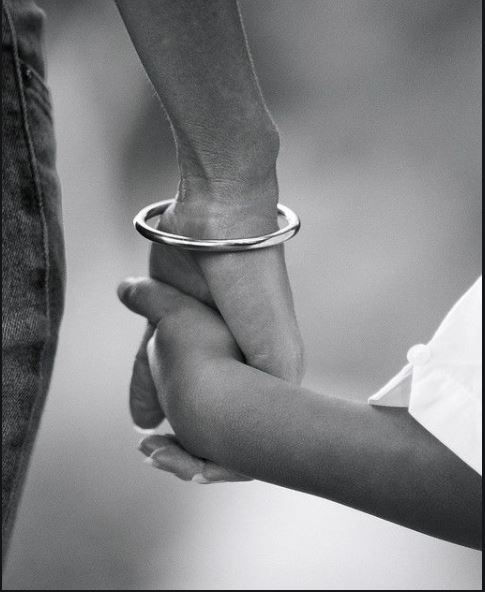

We arrived at the hospital early and walked to the first appointment. In the hallways, I held Sweetie tightly by her wrist, knowing that she could wander away without any safety awareness. I positioned her in a seat far away from the door to minimize escape in the waiting room.

Before being warmly greeted by her primary care physician (PCP), we waited an eternity before meeting her primary care physician (PCP), a young and friendly Indian woman. This was the hospital where Sweetie was first diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (some prefer Autism Spectrum Condition) in 2018 and hyperkinetic childhood disorder.

Upon entering the doctor’s office, I was prepared to be accused of neglecting to provide adequate nutrition for my child, based on my appearance alone – short, black, and fat. After all, Sweetie’s school team suggested ruling out anything medical possibly because they felt her lunches lacked adequate nutrition. After recounting Sweetie’s favorite repetitive diet – bacon, turkey sausage, chicken nuggets, chocolate milk, oranges, and crunchy snacks, I was pleasantly surprised by the PCP’s supportive response. I think it helped that she was a mother as well. She observed that Sweetie’s weight was proportionate to her height. I told the PCP about the spitting and that Sweetie puts everything in her mouth, and she suggested bloodwork to rule out any issues. Although we agreed it sounded more behavioral than medical, we added the bloodwork appointment.

During the exam, Sweetie would not allow the doctor to look in her ears. I was trying to hold her down, and she was pushing back, pushing my hands away, using her entire powerful little 53-pound body to prevent the ear examination. Coaxing and bribes did not work. She was making deep-throated protesting sounds. The PCP let Sweetie play with the otoscope. Sweetie was fascinated by the light on the tip of it and even looked in my ear. At one point, while we were trying to get her to cooperate, she said clearly, “I don’t want that!” - a complete sentence. I was thrilled since most of her communication is one-word responses or gestures. I don’t think I’d ever heard that one. The PCP decided to skip the ear exam to avoid traumatizing Sweetie during her first appointment.

We scooted along to our next appointment, and I was taking precautions to avoid escape. We arrived at the developmental pediatrics department for kids with special needs, and it was at the end of the hallway with double doors. I made sure to sit far away from the doors and position my chair in front of Sweetie's chair. I fed her a snack, peeled an orange, and walked three feet away to toss it in the receptacle. Mistake number 1! Sweetie must have been waiting all day to escape. She zipped through the double doors and flew down the hallway like Flo Jo, beaded braids flying and laughing maniacally. A tall doctor laughed as she whizzed by him.

I did not want to run. I yelled Sweetie’s name with some authority. Nothing. I stood at my end watching her vanishing back and screamed, "Do you want some gum?" At home, a treat usually works to get her to come back to me. Maybe, it was because she missed her whole day at school and all the sensory activities involved. Clearly, she wanted to be free. Mistake number 2! I gave her too much of a head start. By the time I got my two hundred plus pounds moving, it was too late. Everything on my frame moved, from my two-strand twists, the cushy soft flesh on my body to my feet. I forgot about my bad knee trying to catch a mini–Florence-Griffith-Joyner. As I took off, a woman behind me said, "Oh no." I must have been a sight in my huge blue jean shift and gym shoes.

Sweetie turned the corner and I hoped it led to a room, not another hallway. By the time I reached the department, a tall grey-haired black woman pointed left, and I headed that way, so out of breath, I could not talk. I heard a clipped, judgmental female voice asking Sweetie, “Where is your mother, little girl? I entered the room feeling humiliated, gasping for air. Sweetie was on a chair, laughing maniacally, destroying the doctor's room. I grabbed my child's wrist, barely able to release a breathless "thanks" and walked out of that department feeling defeated.

While trying to get my breathing under control, only the strength of my mind made my feet move forward. The nurse practitioner (NP) greeted us with a wave upon our return to developmental pediatrics. They were ready for us. In her office, I plopped down and started talking about the behaviors. Sweetie spat a puddle of chunks on the floor, and I said firmly, "no spitting." The NP said I should ignore the behavior, take the emotion out of it because it reinforced the behavior. She said Sweetie was looking at me while spitting, waiting for a reaction. I am familiar with that theory; however, how does one ignore spitting? It's gross! The NP brought up meds again. We tried medication before to treat her impulsive behavior and increase attention but stopped when Sweetie became aggressive (kicking, pulling my hair, punching) and emotional (crying). Sweetie spat a puddle on the floor again. This time I told the NP, “You caught me at a good time, I just chased her down the hallway." She observed that the spitting was behavioral and recounted her spiel about the meds. I shared the recent data from Sweetie’s OT, Speech Path, and teacher at her therapeutic school – all noted regression and an increase in impulsive behaviors. What should I do?

Sweetie’s final appointment was the bloodwork. My energy was low by this time. We stood in line to sign in for the appointment, and I told the intake worker that my daughter had autism, and I needed support, then I chose a corner seat in the waiting room, on guard. In the tiny office, I reiterated to the phlebotomist that we needed support to hold or distract Sweetie. However, she was calm when the tourniquet was wrapped around her arm. Sweetie picked up a glass tube and I took it from her. The phlebotomist said she can play with that and handed it back. I said, she has no safety awareness and eats plastic and glass, then took it away again. The phlebotomist had the grace to say, “Sorry, Mom.” When it was time to take Sweetie’s blood, that girl screamed like someone was trying to kill her and fought me like I was a woman on the street. The second worker was a young heavy girl, so I felt hopeful. We figured out that I should hold Sweetie in my lap, and she would use her body to keep Sweetie in place and secure her arm while the phlebotomist inserted the needle. Sweetie howled, stopping only to take a breath and the needle was in and it was over. This chick started screaming again. I said something about her being a little diva. My sweet little diva. I’ll never schedule two appointments on one day or allow them to add a third. Lesson learned.

__

__________________________________________________

Vania Johnson is a happy wife and mother of an energetic six-year-old daughter. She works as a school social worker in Chicago, Illinois, and spends her spare time laughing, traveling, and dining out.

Great read! The decision to medicate is always complex and personal. Weighing risks and benefits is key. Best tummy tuck Dubai options can also be life-changing for those considering body confidence!

To win the Nyt Wordle Game, you need to approach each guess strategically. Start by choosing a word that includes different letters from your previous guesses. This will help you narrow down the possible options and eliminate incorrect choices faster.

https://nytwordle.today

Assignment Help Service Near Me is the medication for students, offering timely help and expert advice to alleviate the stress of academic deadlines. Their proximity provides quick support and personalized attention, making them a go-to solution for students in need. I highly recommend their services for anyone looking to ease their academic responsibilities.

The debate on whether to medicate or not is always a tough one, with so many factors to consider. It's crucial to weigh the pros and cons carefully. And hey, speaking of weighing options, why not do it in style with the best men's leather motorcycle jackets? Finding the right balance between comfort and fashion can make any decision-making process a bit easier!

เว็บพนันออนไลน์ที่เปิดให้บริการมานานมากกว่า 10 ปี และได้มีเกมพนันมากมายวให้ท่านได้เลือกเล่นมากกว่าที่อื่น ๆ แน่นอน ซึ่งท่านรู้ไหมว่าทางเว็บของเรานั้นได้มีเกมพนันมากกว่า 100 เกม ให้ท่านได้เลือกเล่น ไม่ว่าจะเป็น แทงบอลออนไลน์ สล็อตออนไลน์ เกมยิงปลาออนไลน์ บาคาร่า รูเล็ตออนไลน์ และยังมีเกมพนันออนไลน์อื่น ๆ อีกมากมายให้ท่านได้เลือกเล่นอีกด้วย ซึ่งเราอยากให้ทุก ๆ ท่านได้เข้ามาเล่นกันได้อย่างเต็มรูปแบบได้เลย